Horizon 2020 is taking shape. In June 2013, negotiators from EU Parliament, the Commission and the Irish Presidency of the Council informally agreed on specific questions dealing with the incoming EU's next research program. This informal Agreement had been seen as a relief, as Universities and research institutions were fearing that the complicated European budgetary process could lead to a “gap” between the 7th Framework Program (ending in December) and the new Horizon 2020 (that will start in early 2014). Moreover, this agreement has already produced some effects, mainly that, at the end of September, the European Commission had released the first Amending Letter to 2014 budget – an amendment that increases H2020 budget for 2014-2015.

In fact, through this document, the Commission asked the budgetary authority to frontload in 2014-2015 €400 million for initiatives that deals with competitiveness (H2020 and other programs) and €2 billion more for youth employment. The Commission stressed that “the frontloaded amounts are fully offset against appropriations within and/or between headings in order to leave unchanged the total annual ceilings of each heading and sub-heading over the period 2014-2020”: that is to say that this frontloaded amounts will not increase the total amount, but just use in advance money which had already been established. In particular, the frontloaded €400 million for research will be divided as follow: €200 million for Horizon 2020 budget in 2014, €150 million for Erasmus and €50 million for COSME.

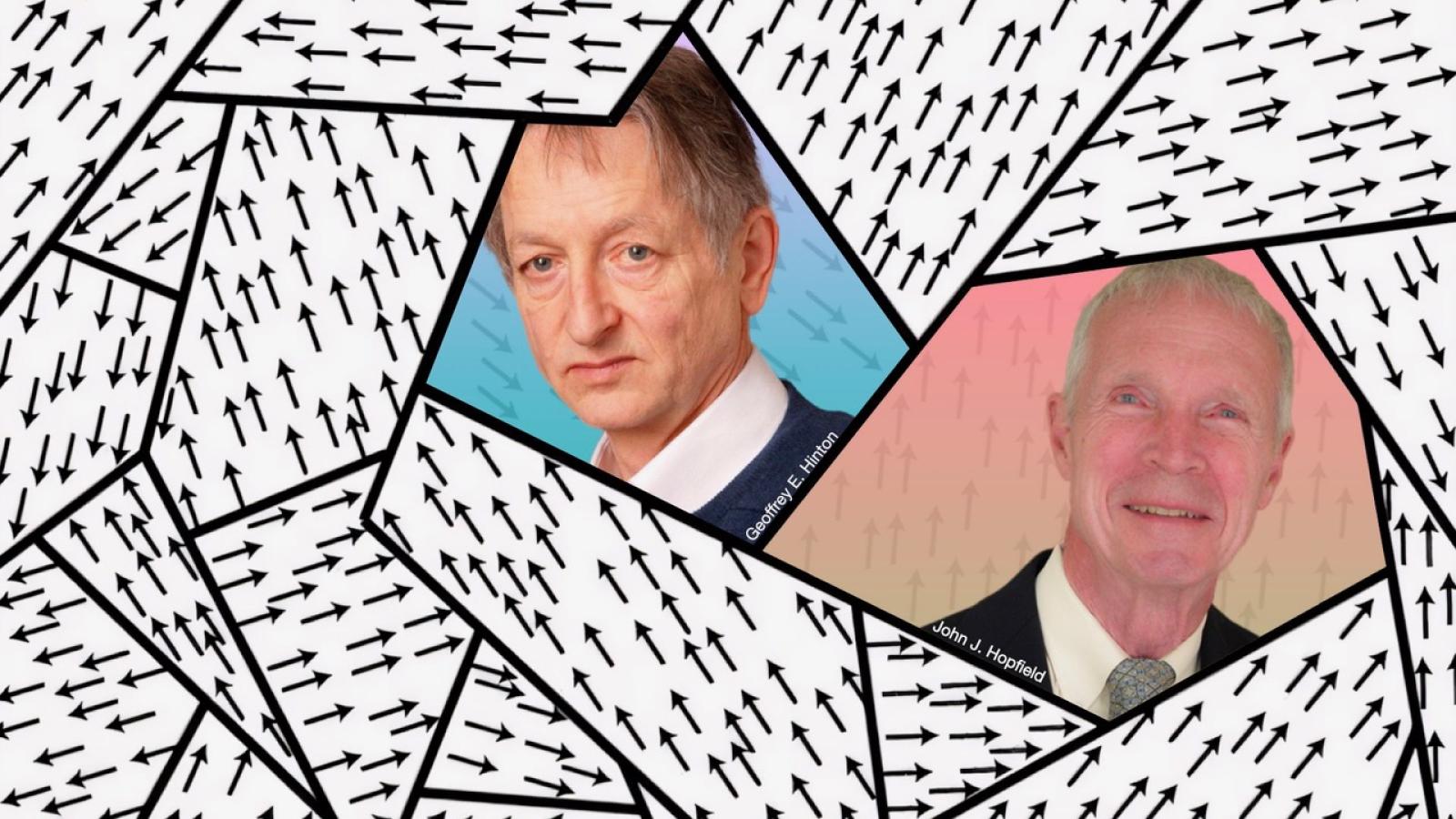

IMG.1: Changes in total amount of H2020 as proposed by the Amending Letter 1 (source)

The amending letter stands on the political need to relaunch research and innovation while Europe is crossing a general economic stagnation. Even though they were more technical questions, also the informal Agreement of June, mentioned above, emerged from a sort of “political clash” between the main EU institutions: the Council, the Commission and the Parliament. The clash was about three aspects: the total amount of H2020 funds, the funding model (that had been the core issue) and some more “socially sensible” issues related to funding.

First of all, in June it came more clear that H2020 would have received €70 billion instead of the initial Commission's provision of €80 billion from the EU's budget until 2020. This was a commonly shared prediction, despite that talks on the EU's budget 2014-2020 are still ongoing. But the main question issued in June was about the funding model. As the Commission and Member States agreed on a reimbursement of indirect research costs through a single flat rate, Universities replied that this would decrease their funding level, asking for the reimbursement of the actual costs in full. In the June Agreement, Parliament endorsed Universities requests, leading Commission and Member States to agree, but maintained the single flat rate, disappointing Universities. Parliament also pushed through some other demands, such as the dedication of almost the entire energy research funds to renewable energies and a Widening Participation budget line that will receive 1% of the total budget to help smaller research groups.

IMG. 2: The budget distribution (in percentage) for Horizon 2020 – June Agreement (source)

The general EU's budget adoption is very complicated: according to art. 314 of the Treaty on the functioning of the EU, the Commission (that represents the entire Union's will) submits a Draft Budget to the Council (Member States will) and the Parliament (Eu citizens will) by 1st September (but usually in May or April). Then before 1st October Council adopts its position, including amending letters by Commission, and passes it to the Parliament, that has 42 days to adopt its amendments on the Council's position. The Council may accept the amendments within 10 days and adopt the draft budget. If not, a Conciliation Committee is set up to adopt a joint text within 21 days. If the conciliatory procedure fails, the Commission has to come up with a new draft budget – the procedure starts again. The ordinary procedure lasts until 31st December.