Paola Annoni – from the Econometrics and Applied Statistics Unit of the Joint Research Centre, Ispra – and Lewis Dijkstra – from the Economic Analysis Unit of the DG Regio, Bruxelles – recently published the EU Regional Competitiveness Index 2013, a competitiveness analysis of European regions. They also measured the regional performances for high education and longlife learning, based on these parameters: graduates rate among people aged 25-64; adult participation to educational or updating programs (lifelong learning); percentage of people who abandoned school at an an early stage (lower level in middle school); university access (number of people living at more than 60 minutes from the nearest university); gender differences. Italy’s picture on higher education and lifelong learning is unmerciful (figure 1).

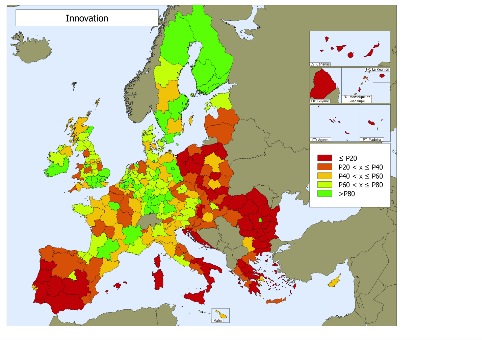

All southern regions are at the lowest level, in company of ex-communist countries only. Central and northern regions, however, are only a step higher. The best of Italy, to be clear, is at the same level of the most undeveloped regions of Western Europe. All Italian regions are alarmingly behind the rest of Europe in regards to high education. Even worse, relative distance with the rest of Europe (and the world) tends to increase. Knowledge is a value by itself. It improves life quality, creates social cohesion and projects toward the future, fostering the capability of creating new things. Therefore, it is no surprising that the picture about innovation is quite similar to the previous one about education (Figure 2).

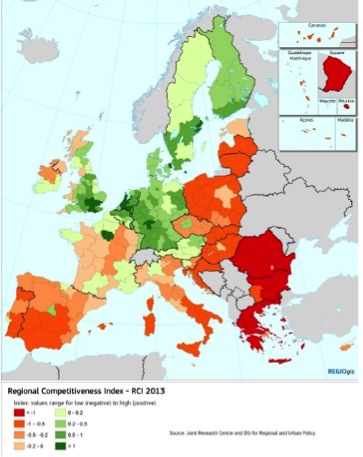

The Annoni-Dijkstra analysis measures innovation capability according to these parameters: patents; creative or knowledge-related jobs; scientific publications; amount of funding in research and development; number of researchers. Two Italian regions only, Lombardy and Lazio, reach the middle/high level of European regions. The other regions in the Centre and in the North lie in the middle/low area. All the regions in the South, but Campania, once again remain in the lowest level. All these factors contribute explaining why Italian Regions have low absolute competitiveness. (Figure 3)

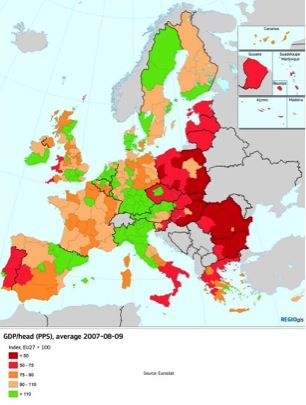

Lombardy is the only Italian region with absolute competitiveness higher (by little) then the European average. All the other regions are below average. The regions in the South, once again, are at the bottom level if we exclude the poorest ex-communist countries (Bulgaria and Romania) and countries undergoing severe crises (Crete and Greece). The description, until this point, is coherent and quite predictable. Innovation and education are essential factors for the competitiveness of a country or of a region. Another picture by Paola Annoni and Lewis Dijkstra, however, presents an anomaly. It is about relative wealth of European regions (Figure 4).

The regional map of wealth per capita shows the South of Italy once again at the lowest step, dramatically coherent with the other figures presented above. The Centre and North of Italy, however, are at the highest absolute level. An anomaly, then, that demands an explanation. How is it possible to be rich and, at the same time, not competitive?

If the competitiveness measurement proposed by Paola Annoni e Lewis Dijkstra is reliable (and it is indeed, since it is coherent with other similar analyses), there might be two possible explanations for this anomaly. Wealth in the North and Centre of Italy is residual, i.e. it comes from competitiveness capability which was high in the past (years or decades ago). In contrast with other high-income regions, the North and the Centre of Italy did not supported education and innovation. In the last few years, they started paying the bill, since their competitiveness has drastically reduced. And wealth is starting diminishing too. The last four years have seen a decrease in absolute terms (because of recession), but in relative terms (in respect to the other European regions) the drop started many years ago. We need to fix this anomaly urgently, if we want to stop Italy’s decline.