When you discover you have cancer, the first and only thought coming to mind is to get rid of it. No one certainly comes out with the rather morbid idea of asking the surgeon for the removed tissue in order to preserve it: throw it away and forget about it. You should instead donate it, because nowadays these samples are precious and coveted.

Researchers around the world would like to have them in abundance and of various types so as to be able to sift through, with current technology, the genes and proteins of cancer cells, in order to identify ever new molecular keys to improve treatment. The analysis of which genes and which specific molecules are present in tumors may provide clues to distinguish between apparently similar types of cancer, those that are bound to grow faster and produce metastasis, or recur after surgery. In particular, tumor samples can be studied to distinguish which types of cancer respond to drugs, especially to the new so-called smart ones, precisely aimed at molecular targets.

For this reason, today almost every trial testing new remedies against cancer also includes the collection of tumor samples removed from patients who agree to participate. And the main sponsors of these trials, the large pharmaceutical companies, are setting up their own bank of tumor tissue, with the idea of keeping them indefinitely as a potential mine of information. This could easily turn into a gold mine, because the stated aim in the near future is to manage marketing any new drug complete with its molecular or genetic test through which the potential beneficiaries of the drug may be identified.

So a race has just began, for which unfortunately no precise rules to prevent abuses and disputes have yet been defined.

With regard to the use of human tissue samples for research purposes, the independent Ethics Committee of the IRCCS Foundation- National Cancer Institute of Milan, in 2008 initiated a process of consultation and sharing of criteria with other IECs available as well as with different actors: researchers, bioethicists, lawyers, patient advocates, industry representatives, experts in regulatory matters.

The process developed through a first meeting, held at the Institute in November 2008, followed by the issue of a first draft consensus document. On this basis, a second round table was organized in June 2009 which ended in November 2009 with a public workshop.

The project resulted in the establishment of a writing committee whose task is to summarize the ethical and legal recommendations in a final document, which is proposed to all interested parties as a basis for discussion.

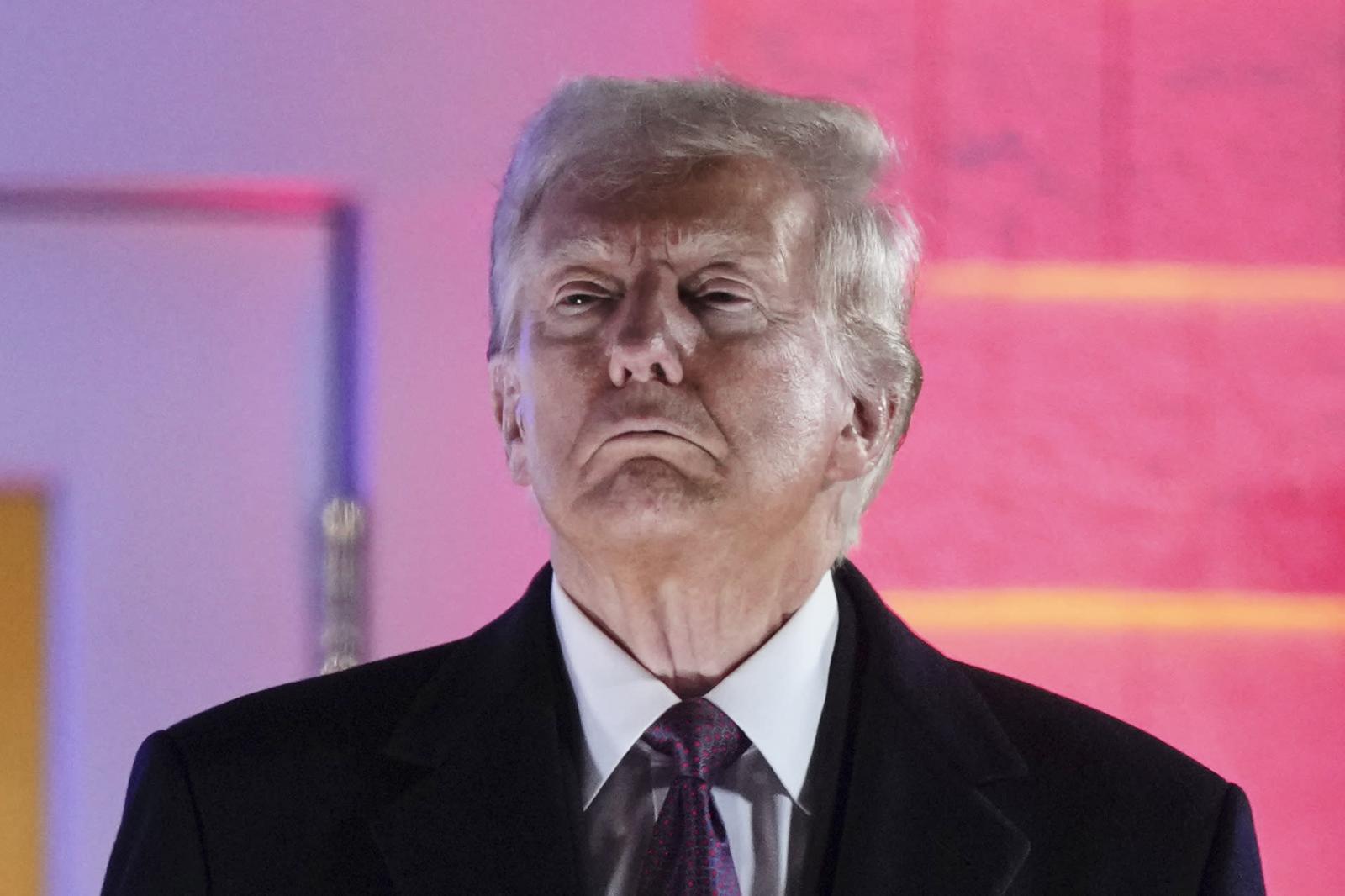

Roberto Satolli is the Chairman of the Ethics Committee of the Cancer Institute of Milan.